According to a recent press release from the European parliament, an EU-wide action plan is requested with ambitious and achievable objectives for phasing-out the use of animals in research and testing new medicines, including timelines for when this process should be complete.

This may be seen as a natural development. Indeed, there are substantial efforts by various stakeholders to reduce the numbers of animals used in research (e.g., by developing alternative methods).

But what if a decision to stop using animals in research comes before alternative methods have become available? This may have a negative impact on the areas where animal use is critical to development of new treatments, and in many of these areas the use of animals is accepted by the society (REF).

Is such a scenario possible? Yes, because those who are against the use of animals in research have a powerful argument – that a significant proportion of our current research is underpowered and involves poorly designed studies where probability of wasting animals is unacceptably high.

We have discussed before (HERE) that this argument can and must be countered asap with just one measure – efforts to increase research quality.

To achieve this, there are two different, but not mutually exclusive, approaches.

According to one strategy (“more but slower”), as many labs as possible (ideally all labs conducting such research) should be convinced to start with small changes – to make addressing these challenges feasible, and easier to accept. In other words, taking one small step at a time but knowing that these small changes will cumulate and together make large impact in the future.

The other strategy (“less but faster”) focuses on a subset of labs that are ready to start and are ready and willing to accept maximal possible quality standards today, in spite of the resource and organizational costs.

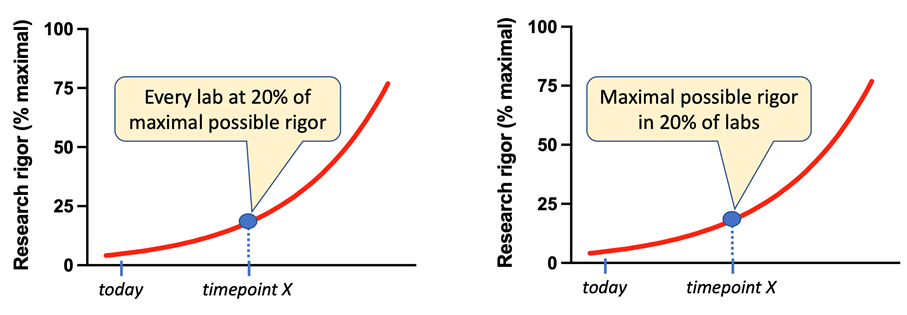

It is interesting that, if there were a way to measure a global average score of research rigor, both strategies may be characterized by a similar change of this global average as a function of time:

However, the difference between these two alternatives becomes obvious in case of a hypothetical scenario where, at a timepoint X (see Figure 1), a decision about the further use of animals in research has to be made:

In the “more but slower” scenario, at timepoint X, every lab has improved but quality is still somewhat low everywhere, and it may take a long (and unknown) time until it finally reaches an acceptable level. Thus, it cannot be justified why research is allowed to continue like this.

In the “less but faster” scenario, at the same timepoint X, there is a certain percentage of labs that deliver high-quality and reliable results and these labs are therefore best positioned to continue advancing science, supporting development of new medications, etc.

Who do we need to call today?

We believe that areas where the need for animal research is most justifiable are also those who are most prepared to implement highest rigor standards; and they should now be firmly encouraged and supported to review their quality practices and, if needed, to improve them. Doing so will serve to increase public confidence in science. Asserting that all animal research in Europe will cease by some specified date in the future provides very little incentive for these important quality improvements. Please do not cut the tree on which we are sitting!

Acknowledgment

The author is grateful to Prof. Malcolm Macleod for the discission and feedback on the earlier version of the above commentary.

0 Comments

Leave A Comment